Can Ukraine convince investors of its good news story?

Still troubled, but not without prospects of an economic revival, can Ukraine overcome political instability and bring investors back? Yuri Bender investigates.-

Ukraine is struggling to find a way into positive news reports. The first few months of 2018 alone saw the deportation of former Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili and the arrest of war heroine turned populist politician Nadiya Savchenko.

After being accused of leading an attempted coup, Ms Savchenko retaliated by accusing the parliament’s speaker of being involved in the killing of the “heavenly hundred” protestors during the pro-EU protest which deposed then president Viktor Yanukvych at the beginning of 2014.

Good news, bad news

Timothy Ash, fixed-income analyst at Bluebay Asset Management and one of the most experienced Ukraine watchers in the City of London, laments that the Savchenko story totally eclipsed the appointment of Yakiv Smoliy to the crucial economic post of governor of the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU), almost a year after the previous incumbent first tendered her resignation.

“On a good news day for Ukraine, with Mr Smoliy appointed as NBU governor, this stuff kicks off,” says a sceptical Mr Ash, a veteran of the “local intrigue” which sets Kiev’s news agenda.

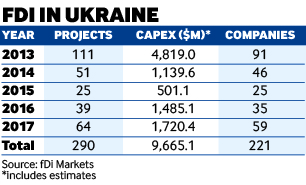

But while analysts broadly welcomed the appointment after a year in central banking limbo as a gateway to unfreezing the latest tranches of a $17.5bn IMF bailout, there are mixed opinions on whether FDI can be attracted back to Ukraine in volumes significant enough to benefit the war-torn economy.

A favourable deal with the IMF is forecast by some analysts for later in 2018, but Mr Ash believes international institutions will lose patience at politicians’ reluctance to impose significant gas price hikes and the president’s stalling around the appointment of judges to a promised anti-corruption court (ACC).

It is time the IMF showed Ukraine more of its tough love, according to Mr Ash, writing in a recent note to investors: “[International financial institutions] need to do some straight talking to [president Petro] Poroshenko and his team, but also to the market, to make it clear where exactly we are in terms of the state of the current programme. Make it clear that if [there are] no gas price hikes [or no] independent ACC, then [there will be] no next tranche.”

Early days

Many analyses of Ukraine have focused on negative aspects of the economy, identifying challenges rather than opportunities.

Inna Zhuranskaya, CEO of Allrise Financial Group, a private equity lending group with operations in Ukraine and Russia, says that Ukraine’s economy is still at an early stage in its historical development, passing through a phase experienced by other central and eastern European (CEE) countries during the 1980s and 1990s. “The country is still in its toddler stage, where the new economic institutions are being set up and their credibility is tested by local and international investors,” she says.

The view from these institutions on the ground is that Ukraine can do more to accelerate socio-economic and governance reforms to “kick-start and accelerate economic growth to improve the standards of living of its population at large and bring it closer to that of neighbouring CEE countries”, according to Ms Zhuranskaya. She is concerned that a constant brain drain of Ukraine's most talented workers will continue as long as the median income remains at just 21% of the European average.

But underneath the political hype and the big macro-economic stories, there are attractive sectors for investment emerging within the Ukrainian economy.

According to Allrise, these sectors include agriculture, banking (because economically crucial smaller businesses are hugely underbanked) and healthcare (including spa resorts), plus real estate-related investments including logistics and premises devoted to mass-market retail and offices for domestic companies.

SMEs hold the key

The revitalisation and regulation of the SME sector is also encouraging, according to Allrise, with an increased recognition from the country’s government that “the SME is the foundation of the modern state, and the level of development of this business is used as an indicator of Ukraine’s sustainable economic development”, according to Ms Zhuranskaya.

The three key regulatory reforms in Ukraine, as identified by Allrise, are: the simplification of SME licensing; a move to EU legislation and standards making it easier to trade with Western partners; and the introduction of the ProZorro system of open public tenders for procurements. As a result of these reforms, she says the ease of doing business in Ukraine according to World Bank figures has improved, as has Moody’s sovereign rating of Ukraine.

If reforms in the energy sector continue, investors will come in larger numbers, according to Makar Paseniuk, managing partner at Investment Capital Ukraine, a private equity and alternative asset management business. He also highlights the country’s “global competitive advantage in agriculture and infrastructure, with plenty of opportunities to generate attractive returns in both sectors”.

Distressed debt is also an exciting area, Mr Paseniuk adds, with Ukraine currently accounting for the highest ratio of non-performing loans in the CEE region. “Recent reforms have improved the regulatory regime for creditors and debt restructuring, creating an opportunity for foreign investment in partnership with local market experts,” he says.

Rich soil

The agriculture sector is currently the most attractive part of the Ukrainian economy for foreign investors, according to Bate Toms, chairman of the British Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce in Kiev. “Ukraine is heading towards becoming the world’s leading grain producer,” he says. “With nearly 40% of the world’s black earth, Ukraine can become the Saudi Arabia of food production.”

Other major exporters are suffering either from climate change or rapidly growing populations, which will fast deplete their food supplies. “Food prices right now are relatively low, as we are still near the bottom of the cycle,” says Mr Toms. “It only takes one major catastrophe to send food prices into an upward trend rather quickly.”

Ukraine’s main challenge, he believes, lies in communicating the country’s success stories to potential foreign investors in the face of sustained Russian propaganda.

Mr Poroshenko’s authorities, he says, have been responsible for bringing inflation down from 100% to 10%, have successfully reformed a troubled banking system and built the second largest army in Europe. “Mr Poroshenko has been hugely successful,” says Mr Toms. “Ukraine is thriving and you can feel the economy on the way up again.”

Battle of the populists

Both populist politician Nadiya Savchenko and former Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili are the type of controversial, colourful characters who thrive in the highly personalised, fast-moving theatre of Ukrainian politics, where envelopes are regularly passed from businesses to politicians, creating a perpetually thin line between state office and penitentiary.

The exiled Georgian Mr Saakashvili (interviewed in the October/November 2017 issue of fDi), a fluent Ukrainian speaker, had been granted citizenship by his old college friend, president Petro Poroshenko. Mr Saakashvili created waves as he preached an anti-corruption agenda as governor in the southern port city of Odessa, but fell foul of Mr Poroshenko when his popularity and political agenda began to eclipse that of the president, and he had his citizenship removed.

While he had high-fived his way around the western city of Lviv, after illegally breaking the border in the autumn of 2017, challenging the authorities to arrest him and fight off his minders, by the winter the public had tired of his rants, his star faded and he was quickly flown to Poland after being bundled out of a Kiev restaurant.

Ms Savchenko, nicknamed ‘Ukraine’s Joan of Arc’ after being abducted by paramilitaries and smuggled into Russia before being held in jail for two years, returned to a heroine’s welcome after Mr Poroshenko flew her home on his presidential plane as part of a prisoner swap in 2016. She quickly entered the political arena, but also fell out with the presidential court and has been accused by prosecutor-general Yuri Lutsenko, a Poroshenko ally and himself a former political prisoner, of plotting a military coup.

Both characters have their own constituencies. Mr Saakashvili had a small army of armed, apparently loyal followers, ready to fight their way out of any situation. They include several ex-gangsters and paramilitaries, who have worked for various often competing factions.

Ms Savchenko has a queue of callers on late-night TV about her vision and policies for the country’s future. But for most Ukrainians, the fact that both figures receive so much TV airtime, compared with their rivals, is evidence that they are backed by business and media barons who want to change the political status quo, or else foes across the eastern border, keen to distract voters from any economic progress. Their reform agendas – rightly or wrongly – are seen as being dictated by their paymasters.

While some Western politicians have backed Mr Saakashvili’s political ambitions, one Ukrainian commentator told fDi: “The solution and the leader is likely to come from inside the country rather than being parachuted in from elsewhere. I cannot remember any examples in history, after Catherine the Great, when such ‘implantation of leadership’ was successful.”

Global greenfield investment trends

Crossborder investment monitor

|

|

fDi Markets is the only online database tracking crossborder greenfield investment covering all sectors and countries worldwide. It provides real-time monitoring of investment projects, capital investment and job creation with powerful tools to track and profile companies investing overseas.

Corporate location benchmarking tool

fDi Benchmark is the only online tool to benchmark the competitiveness of countries and cities in over 50 sectors. Its comprehensive location data series covers the main cost and quality competitiveness indicators for over 300 locations around the world.

Research report

fDi Intelligence provides customised reports and data research which deliver vital business intelligence to corporations, investment promotion agencies, economic development organisations, consulting firms and research institutions.

Find out more.